Okay, we get it. Sometimes, talking to your friend or relative with cancer feels awkward. What do you say? What if you say the wrong thing? How can you help?

Recently, a discussion in our private Facebook group took off – “What’s the silliest thing someone has ever said to you about cancer?” asked David, one of our members. More than 110 comments later, we felt like we had to share some of them with the world! Take a read and let us know what you think. If you’ve got cancer, we hope you’ve managed to avoid these comments (all of these are real, by the way – we haven’t made them up!). If you’re supporting someone with cancer, we know you want to help. Stuck for words? Sometimes admitting, “I don’t know what to say” can be the best way forward.

1. “You don’t look like you have cancer”.

In the movies or on TV, the person with chemo usually spends their days losing their hair and looking increasingly ill. But these days, a lot of cancer drugs don’t make you lose

All of these people have, or have had cancer.

your hair, and many people don’t have chemotherapy anyway. Some people end up on “watch and wait” without treatment right away, while surgery and radiotherapy are frequently given for more localised cancers (or even advanced cancer if they can halt the spread). The key message here? A lot of people don’t “look” like they have cancer but just because you can’t see the side effects of the cancer or treatment doesn’t mean they aren’t there. A simple “How are you feeling?” can be a much better, and more sensitive way to start a conversation.

2. “So, how long have you got?” or “I’ll help you with your bucket list.”

We all know that cancer can cause death. But if, when, and how that might happen isn’t usually something that we want to talk about. When you’re asking your friend or relative about their illness, ask yourself whether your questions are more for your own information (read: nosiness) or to help them.

Most people with cancer aren’t given a “timeline”, and even if they are, they might not want to share it. If your friend is openly creating a bucket list, great, but generally speaking it’s good to keep the death talk to a minimum. Journalist Helen Fawkes created a “List for Living” after she was diagnosed; this can be a much more positive way to think about treating someone with cancer to a nice experience than a “bucket list”.

3. “You don’t need chemo…..I know someone who cured their cancer with [insert questionable cure here]” or “Chemo doesn’t work – it’s just a plot by Big Pharma to make money” or “Have you tried turmeric?”

This will not cure your cancer.

So, your friend is prepping to start chemo and this seems like a good time to tell them about an article you read about someone who shunned chemo and cured their Very Deadly Cancer with kale and wheatgrass, right? Wrong.

Chemo can be tough but it saves lives, and whether you agree with your friend’s treatment decisions doesn’t matter. Eating more fruits and vegetables, and getting more exercise is certainly good for us and there is some evidence that it can help reduce rates of relapse in certain cancer types. But if the person you’re supporting is undergoing chemotherapy, consider carefully whether it’s definitely the right time to bring up that raw food diet that your aunt’s sister’s best friend used to cure her dog’s leukaemia. It’s probably not. Instead, why not make them a nice meal and take it over to their house? (Only include kale if you know they like it!).

4. “That’s a good kind of cancer” or “At least you’ve lost weight. There’s a silver lining in everything, right?”

When you’re diagnosed with a life-threatening disease it’s pretty hard to find any silver linings. Self-esteem can take a massive hit, so try to avoid making comments about someone’s appearance or weight or downplaying the seriousness of what they’re facing. Anyone diagnosed with cancer is likely to feel pretty shocked by the diagnosis. Sure, some cancer types are more curable than others, but as most oncologists will tell you, every case is different. Telling someone they’ve got a “good cancer” risks minimising their feelings. A better approach might be to say something like “I’m so sorry about your diagnosis. Do you want to talk?”

5. “Cancer is caused by past trauma and stress”

There is little good quality evidence that stress and cancer are linked and if your friend has cancer, they’re probably stressed because, you know, they’ve got cancer. Ask yourself what you can do to relieve their stress. Can you take them out for a film or a drink? Cook them dinner? Walk their dog? It doesn’t need to be a big thing – even small gestures can mean a lot. Take a look at our blog about how you can help.

6. “I’ve heard that’s a really bad way to die” or “I know someone who died of that.”

As with point 2 above, avoiding death talk is generally the way to go. Talking about how bad/painful/awful death might be is a big no no. And telling your friend or relative with cancer that you know someone who died of the exact same thing is also to be avoided. Know someone who has lived 20 years after a diagnosis? Feel free to mention them! Those are the stories we like.

7. “Managing someone with cancer will look good on my CV” or “What about me?”

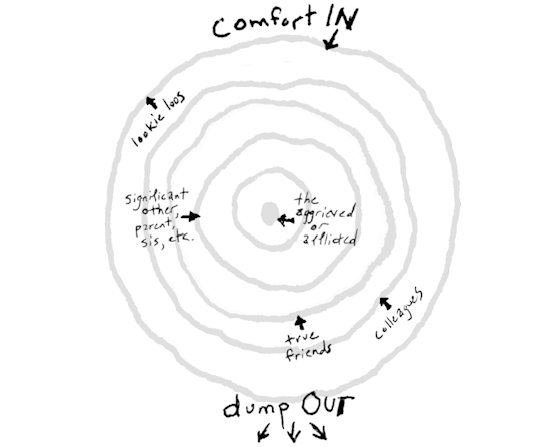

If someone you know has cancer, it’s time to think about all the great ways that you can support them. A cancer diagnosis is about the person who has cancer and those immediately surrounding them (partners, parents, children). This can feel odd if you’re used to getting support from your friend or relative but think of it as a good opportunity to repay all the love and support that you’ve received in the past. Unsure who to turn to for support? Take a look at this handy “ring theory” guide and remember: support in, dump out!

8. “If you need anything, just let me know.”

We know it might sound odd, but often, we don’t know what we need, and even if we do, it can feel scary to ask. Rather than making your offer general, try to make it a bit more specific. Ask if you can make dinner on a Tuesday, drive your friend to their next appointment, or do their grocery shopping next week. By making it specific, you’re taking away the burden of coming up with something – and that is helpful.

9.“Everyone dies” or “Any one of us could get hit by a bus tomorrow”.

“I might get hit by a bus tomorrow”.

You’re right – everyone does die. But the difference with cancer, especially cancer at a young age, is that death goes from being a vague hypothetical, to something that is giving you a cold hard slap in the face. That bus everyone’s talking about? Your friend has already been hit by it. They’re just waiting to see whether they’ll survive, and they’re likely really scared. It’s great to ask someone if they want to talk but sometimes distraction can be the greatest gift. Seen a funny cat video online? Now may be the time to send it over (assuming you’ve already checked on how they’re feeling).

10. “So, you’re all better now, right?”

One of the things that few people talk about is the long-term effects of cancer. The media shows us people who have survived cancer and go on to run a marathon or write a best seller. What you don’t get to see is that those same people are often also left scarred, depressed and tired after months or years of intensive treatment. For many people with cancer, the end of treatment is a tough time. They’re no longer seeing their doctors and nurses as regularly and, on the surface, life appears to be returning to normal. They may be in remission or be looking forward to a long treatment break but they’re unlikely to be “all better now” or for a long time to come.

We know it can be tough to keep up the same level of support once treatment has finished but keep in mind that your friend or relative may be feeling especially lonely. Make sure to keep checking in and, if you can, make sure they still get the odd treat. Be ready to chat if they want to talk about how they’re feeling and remember that you don’t have to solve all their problems. Just being a good listener can be all that’s needed.

If you’re in your 20s, 30s or 40s, why not join us online? We’ve got a private Facebook group here, or you can follow us on Twitter or Instagram.